Mudlarking: Combining Passions

By Kate Wiseman

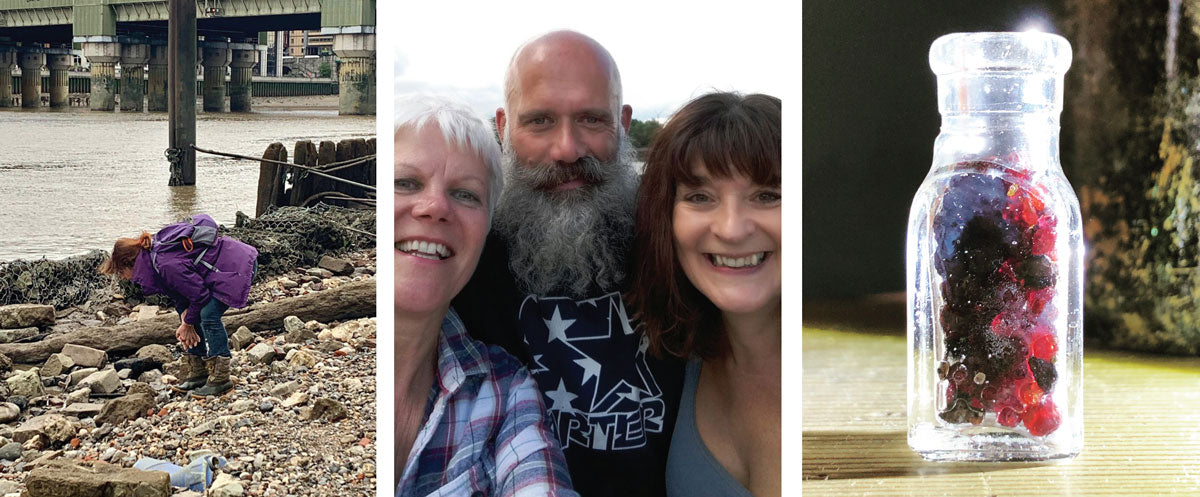

It was a windy day in Greenwich, London, home to the Cutty Sark tea clipper, the much-loved Chelsea pensioners, and the Royal Maritime Museum, and my friend, Joy, and I were impatiently waiting for the arrival of an acquaintance who was to take us on a treasure hunt along the foreshore. This would be my first experience of mudlarking and one of the most exciting days of my life. Our guide turned out to be a fount of knowledge, and his expertise in pinpointing treasures hidden by mud and rubble was astonishing.

“Look for places where the tide has washed away some of the debris,” he said. “Always check out patches where you can see lots of old metal. The river likes to be tidy; she deposits things of a similar weight together. If you can see nails and old bits of metal, there may be coins or jewelry, too.”

I asked endless questions, and our guide answered them all with limitless patience. “Yes, the fouled anchor on that button means that it fell from the jacket of a naval man,” and, “Yes, Kate, that does look like a huge uncut emerald, but it’s actually a lump of broken glass,” and, “Kate, I’m afraid that chunk of painted stone is unlikely to be from a Tudor palace. I may be wrong, but it looks to me as if a child has daubed it with paint and thrown it in the river. Maybe three months ago. Sometimes schools do things like that.” That man had the patience of a saint, and without further ado, I was hooked on mudlarking.

I got my three-year Thames Foreshore Permit, and although I don’t live particularly close to London, I went there whenever I could, eventually “getting my eye in” as mudlarks call the ability to spot the things that lay camouflaged on the foreshore. I found the odd, interesting piece, and a host of marbles in the mud of the estuary village where I was living, but nothing that would make an attention-grabbing headline for one of the many mudlarking groups on social media. I didn’t care. The pins, pottery and pipe stems were all treasure to me—little pieces of history that seemed to dissolve the gap between past and present.

To touch a fist-sized piece of Roman mosaic floor just revealed by the tide, to know that the person who stuck those tesserae haphazardly into the knobbly cement had lived two thousand years ago, is to throw open the doors of time. I imagine the mosaic maker, a short man, clean shaven as Romans and Roman acolytes liked to be, hurriedly poking the little squares of white marble into place. Maybe it had been the end of his day and he wanted to get home. Maybe he was daydreaming of Rome and wondering if he would ever get to see it for himself. Maybe he had backache from bending over all day. For two millennia, while kings and queens reigned and fell, while London burned and plague raged, that man’s handiwork waited to be found. And I was the one who picked it up—the first person to touch it for years too numerous to count. The thought takes my breath away.

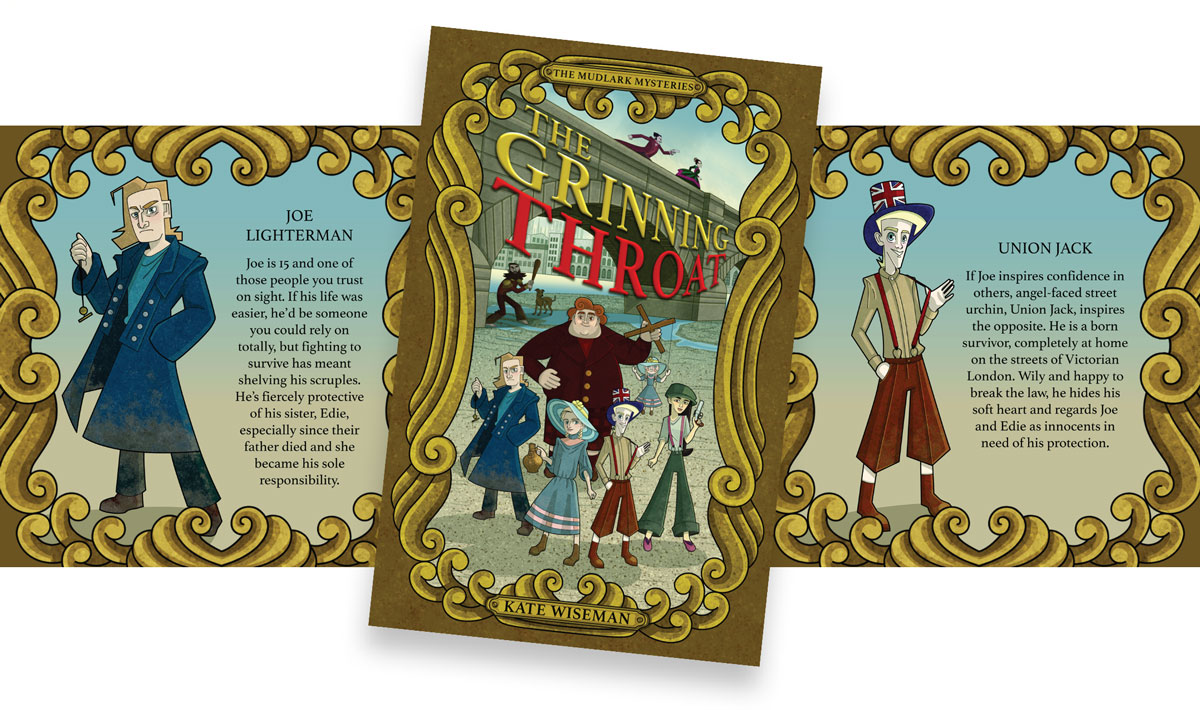

My other passion is writing, and I am very lucky to have novels published in several countries. Mudlarking is growing in popularity very quickly, and there are an increasing number of books about the subject appearing on the market. I buy each one, carefully arranging them to form my own small library on the subject closest to my heart. I read with pity about the hard lives of nineteenth-century mudlarks. More often than not they were children without homes or parents, or old people with no family to look after them. I realized, with astonishment, that there was hardly any fiction on the subject, and I decided that it was a gap I was destined to fill.

As a lover of history, it seemed natural to set my novels in the days when mudlarks abounded and when it was a survival tactic, not a wonderful hobby. My characters seemed to develop without much help from me. The surname of the central characters, siblings Joe and Edie Lighterman, is a homage to a very common Victorian Thames-side occupation. Lightermen transferred the cargo from the teeming ships that used to moor in the Thames, to the shore. There were so many of them that they sometimes had to wait for weeks, their precious cargo guarded by a skeleton crew, for the lightermen to unload it onto huge flat-bottomed boats called lighters (because they lightened the ships of their cargo) and take it on its onward journey.

I’m loving writing the Mudlark Mysteries and hope that there will be many more to come. I also hope that my nineteenth-century mudlarks pass some of their amazing luck to me. They always seem to be finding astonishing treasure that plunges them into adventure after adventure. I’d be happy with just one of their finds: a silver pocket watch with an undecipherable note tucked into its casing; a golden Aztec skull; an Egyptian cat fashioned in lapis lazuli. It would have pride of place among my Thames treasures and would certainly make the others—spent bullets from two world wars, sherds of beautiful pottery that I make into mosaic tables, and tiny doll limbs—look a bit shabby. But I will still love them all. They’re all treasure to me.

Look for The Grinning Throat: Mudlark Mystery Number One, released in July 2023.

Learn more about mudlarking

Learn more about the experiences of mudlarks, who search the shores of rivers, bays, and seas for historical finds and other objects. Articles ›

Mudlarking on the Thames Foreshore requires a permit. Learn about rules for mudlarking in London ›

All photos courtesy of Kate Wiseman.

This article appeared in the Beachcombing Volume 37: July/August 2023.